2.1- Sabrina of the Severn

For the start of season two, we’re looking at the tragic, haunting tale of the princess-turned-water sprite Sabrina. This story comes to us via our old friend Geoffrey of Monmouth as part of the long cycle that tells of the founding of Britain. Sabrina’s death and reawakening have served as inspiration for artists throughout the centuries. Let have a look at some of the sources, inspiration and transformations the story has undergone since it was first published in around 1136.

Brutus, Cornieus and Gwendoline

Sabrina’s story starts at the end of the reign of the famous Brutus, who we have seen before in the tale of Cormoran the Giant. Like many British medieval writers, Geoffrey of Monmouth seems to be trying to give Britain the legitimacy of a connection to the ancient worlds of Greek and Roman Literature. In Historia Regum Britanniae, he tells of the Trojan Brutus’s conquest of Britain, the setting up of the kingdoms of Britain under Brutus’s lieutenant, Cornieus, and his sons Locrinus, Camber and Albanactus.

The only one of these men we’re interested in is Locrinus, who apparently becomes king of Loegria (England) after his father’s death. Betrothed to Cornieus’s daughter Gwendoline, he falls in love with a captured German princess and proceeds to have a daughter with her, Hafren.

When Cornieus dies, Locrinus sets aside Gwendoline in favour of the German princess and her daughter. In the inevitable war that follows, Hafren and her mother are captured by Gwendoline and thrown into the river to drown. Thus a legend is born.

Hafren or Sabrina?

In Geoffrey’s telling the unfortunate daughter of Locrinus is named Hafren, which is one of the Welsh versions of the name of the River Severn. In fact, the Romanised name Sabrina had been used for both the river and the girl as early as the 2nd century AD. As with almost everything else in the Historia Regum Britanniae, the quasi-historical tales of Hafren is Geoffrey’s own re-telling of a much older legend which appears to have predated the Roman occupation of Britain. And as with the story of Vortigern and Ambrosius, Geoffrey seems to have opted for Welsh names over the Latin or Celtic.

But it is impossible to tell whether the girl or the name of the river came first. Is the story of Sabrina just a way to explain how the river got its name? Or is this the personification of the waters by a people who believed that rivers and lakes were the entrance to another world?

The British Celts used waterways as sites of worship, as evidenced by the huge number of votive offerings found in rivers all over England. But the Severn seems to be almost unique in being named after its protecting goddess. Most other river names, such as the Avon, Wye, Wyre and Don, are derived from Celtic words for water. And others, such as the Thames, Teme and Tamar, seem to be dervided from Celtic words for ‘dark’, which is perhaps a description of their waters.

Sabrina Fair

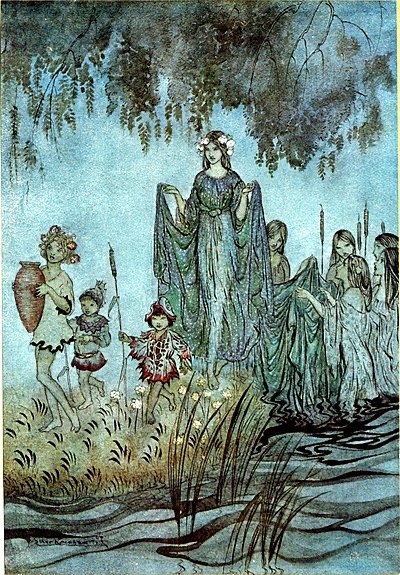

The story of Sabrina is so irresistibly tragic that it comes as no surprise that it has inspired writers and artists throughout the centuries. Edmund Spencer includes as passage about the sprite Sabrina in ‘The Faerie Queen’ and John Milton used the goddess in his masque ‘Comus’, which is about chastity. In the story, he presents the transformed princess as a divine nymph who saves a virgin from being seduced by a villain. If you haven’t read it then there is a full copy available here. The imagery paints a wonderful illusion of divine beauty:

In twisted braids of lilies knitting

The loose train of thy amber-dropping hair;

——Listen for dear honour's sake,

——Goddess of the silver lake,

Listen and save!

In the twentieth century, Milton’s words would lend themselves to the play Sabrina Fair which then became the icon film starring Audrey Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart.